This past month I hit a wall in my work-in-progress. I really struggled revising the end of a chapter and making it feel ~complete. What I wrote was fine, but it wasn’t really good, and it didn’t do the things a chapter end should do (specifically both wrap up and carry forward). And the whole frustrating experience made me think a lot about when writers should ask for help and what kind of help they should seek.

In general, my advice for writers is that they take a story as far as they can independently before asking for outside feedback and assistance. What that means will vary writer to writer and project to project. Sometimes that might be the end of a second draft, and other times the end of a fourth or fifth draft. Or sometimes it might be the end of one specific chapter that is driving you to drink and perhaps you just desperately need someone who can see the forest instead of every damn tree!

Ahem.

The kind of feedback a writer seeks depends on what they are prepared to do with the story after receiving feedback. Sometimes, like in my chapter, I need someone who can be a genius and help me pinpoint what’s wrong. That’s when I need focused feedback that will lead to a revision. Other times I really am just looking for positive reinforcement. For someone not just to tell me something doesn’t suck, but to say that it’s good (maybe even great).

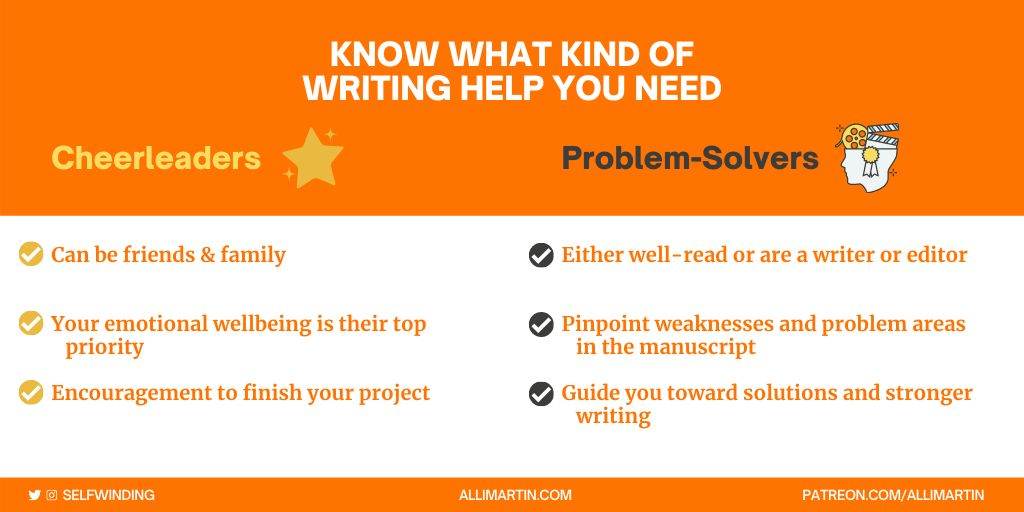

The latter type of feedback is performed by Cheerleaders, and the former we’ll classify as the work of Problem-Solvers.

Cheerleaders usually come from your friends and family. They’re people who care about your emotional wellbeing more than your writing. They’re not going to lie to you, but they aren’t going to nitpick your grammar either. Cheerleaders are so important during a first draft to encourage you to keep translating your story from thoughts to prose, but they can also be important during revision while you’re crafting that first draft mess into an understandable narrative. Cheerleading support can take the form of an enthusiastic first reader or an accountability partner, or someone else who is generally excited every time you tell them you put words on the page. Cheerleaders help you finish whatever stage of the project you’re on, but they don’t help you make your writing better.

Problem-Solvers can come from your friends and family but should be familiar with your genre and are preferably either well-read or are a writer or editor. They’re going to help you pinpoint weaknesses and problem areas and, hopefully, guide you toward solutions and stronger writing. (Solution guidance is sometimes, “Have you tried X? Y? Z? AA? Etc.”) Problem-solvers are helpful when you’re stuck in a revision quagmire and can’t figure a way out (or can’t decide if the revision does the thing you need it to do). Their feedback can help you make a list of issues to address in your next revision or identify ways to polish up a nearly there piece. You can hire a problem-solver (hello), but if you’re hiring work, absolutely have a complete draft of your manuscript—you’ll get much better, more comprehensive feedback if the editor can see the whole forest.

Whether you’re looking for actionable feedback or for support, know what you need and what to ask for. I didn’t get Problem-Solver help on my end of chapter conundrum, but the Cheerleading I received encouraged me to move on and not waste time agonizing since I had another chapter to revise. The time away from the chapter allowed me to figure out what was wrong, and when I went back for a final revision—hooray! The chapter now wraps up and carries forward. So while thinking about where to get advice, never forget that the best adviser you have for your writing might be yourself.

For full access to The Write Life, sign up on Patreon for $1 or more per month. You’ll also receive a personalized thank you in a future edition of The Write Life.