Welcome writers, readers, and inspiration chasers! Join me as I dip into my prompt resources and select something to explore and share. These prompts are all about inspiration—what they inspire for me and what they inspire for you.

If you’re inspired by the prompt, whether that’s by creating something epic or just warming up for your creative day, I hope you’ll share your creation.

This prompt comes from The Lover’s Dictionary by David Levithan. The words defined in The Lover’s Dictionary create a story, and just as Levithan uses those definitions to construct a novel, so too can you take a word and definition and retool it for your own creative purposes.

Feel free to go wherever the prompt takes you!

ersatz (adj)

Sometimes we’d go to a party and I’d feel like an artificial boyfriend…

Where I started:

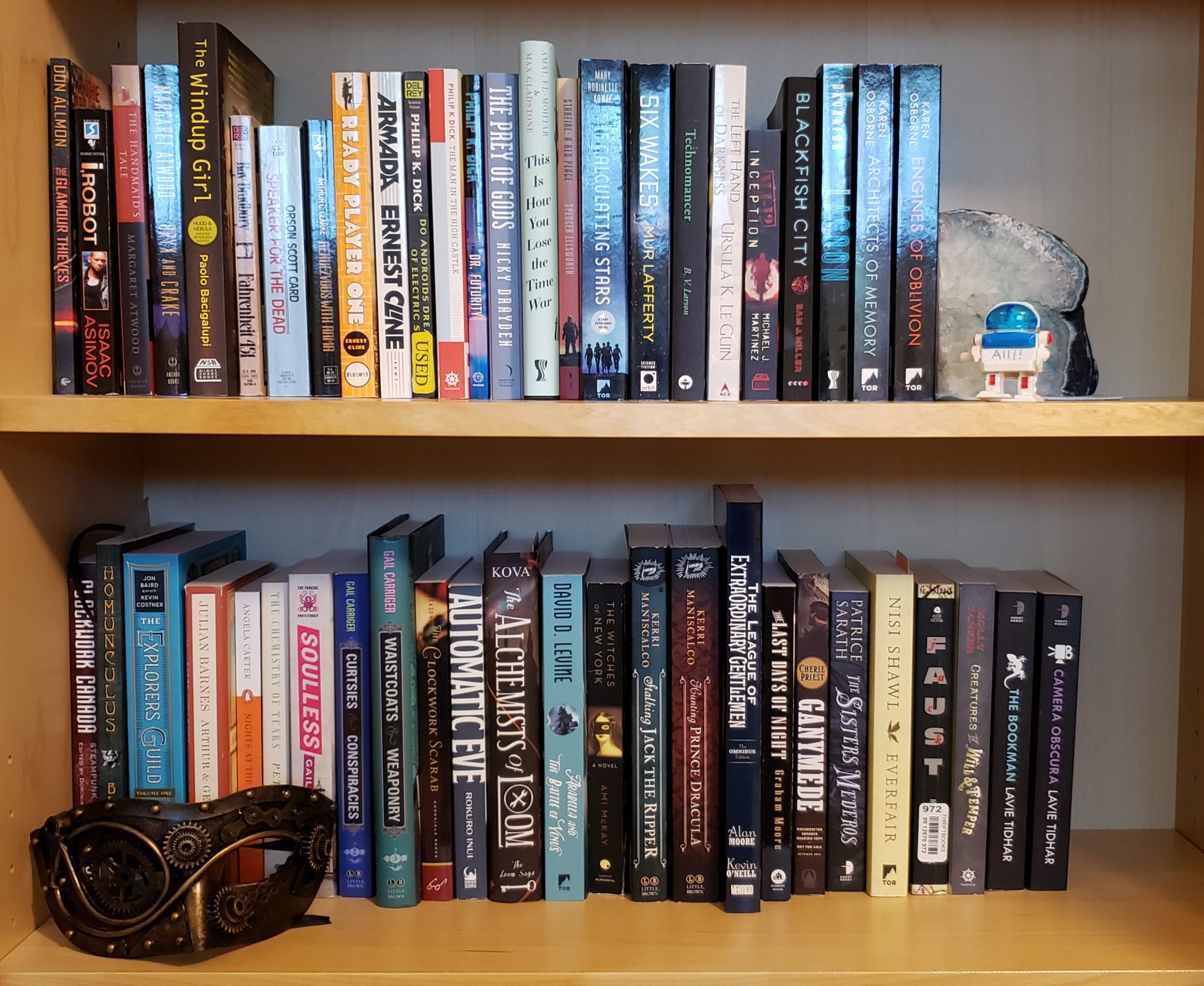

The word “ersatz” is forever linked in my memory to Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Phillip K. Dick, so this prompt immediately brought to mind replicants and androids.

The rest of the prompt—an artificial boyfriend—reminded me of an idea cultivated by my writing group. We wanted to put together an anthology of stories based around the people who rent artificial friends. These android friends can fill any need, the person in the friend group who takes all the pictures, the best friend of a shy individual, or an impressive date to a high school reunion… which is the direction I took the prompt for this snippet.

A high school reunion is a place where a person wants to be seen as visibly successful. Short of being crowned during the proceedings, that typically translates to an enviable physical appearance and a stable romantic partner. Many other rom-coms have already trod the path of bringing a fake date to a high school reunion, I just put more emphasis on the “fake” part of the scenario, giving dear Kay her own artificial boyfriend.

(One day I am putting together this anthology—mark my words.)

Originally posted for the Story Kernels Patreon Oct 7, 2022.

What I wrote:

Kay smiled broadly as she stepped under the balloon archway. Welcome Back Sycamore High Class of ’99 screamed from nearly every wall of the hotel ballroom. Clint’s arm kept her upright as they approached the check-in table.

This was such a bad idea.

“Everything’s fine,” Clint whispered. His voice modulated perfectly so only Kay could hear him. “We’ll stay an hour, make sure to be seen by the right people, and I’ll sing all your praises.”

Kay clutched his hand, which suddenly felt smoother and less lifelike than it had when she’d picked him up at the Fast Friends facility. “You know not literally, right? Like, don’t sing.”

Clint chuckled softly, his smile pleasant and perfect, and exactly the kind of man Kay’s high school friends had expected her to marry. “It’s an expression, Kay. I promise, FF’s programming is flawless.”

No one near them reacted, everyone lost in their own conversations as the line inched forward. Still. “Don’t say the p-word,” Kay muttered.

“Then don’t question my p-word.”

The man in front of them turned around abruptly, eyes wide, and Kay laughed through her intense blush. She could only imagine what p-word he thought they meant.

Now it’s your turn:

What might be fake in your scenario? Who is the artificial boyfriend and how are they artificial? Is the artificial feeling a constant or situational?

If you enjoyed this prompt and would like another, the June prompt on Patreon inspired a story about a woman silencing the petty man who had imprisoned her.