I’m great at meeting metric-based goals, but in meeting those goals I sometimes lose sight of the goals driving those metrics. I can write a specific number of words, but those words don’t always resolve into completed works. I know creatives who struggle with figuring out how to break big goals (like “write a novel”) into smaller, more manageable tasks. And I know other creatives who set goals, get distracted, and when they look up again, the whole year is gone!

In an effort to stay focused, this year I decided to break my goals into smaller, targeted tasks that can each be completed in about a month. These are designed to focus my attention, make progress in specific ways, and measure my overall progress with landmarks.

I provided an overview of the Writer’s Five in my January Write Life post, A Contemplative January, but now I’m coming to you with a resource to facilitate writing and tracking your goals.

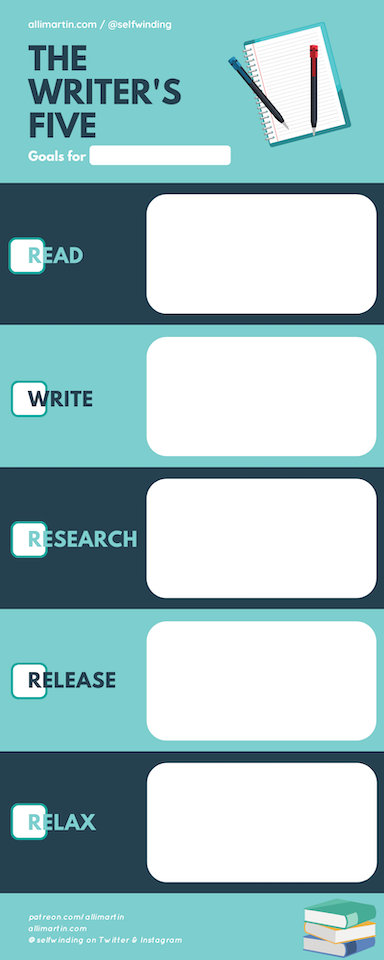

Resource: Writer’s Five Worksheet

The Writer’s Five Worksheet is a blank sheet for you to write and track your goals for the month. Each goal is based around one verb: read, write, research, release, and relax. Basing the goals around a simple verb already tells you a lot about what your goals will be, thus making them easier to compose.

For each goal, name one specific thing you will do. Make sure it’s something you can accomplish in about a month, so “Write a novel” shouldn’t be on your list, but maybe “Write Chapter 1” will be.

Read: Name a specific book you will read.

If you have other reading goals and are a regular reader, I encourage you to select a book (or two) you’ve either been struggling to read or putting off for some reason. One of the books I selected for February was a book I started six months ago and just hadn’t finished. You might also select books you “should” be reading, such as a book published in your genre in the last five years.

Write: Name a specific project and the part of the project you will write.

You might focus on a single chapter or section of your novel, or a specific stage of writing, for example, “Revise short story.” Remember, the task doesn’t have to take a month to finish, but should be small enough to complete within a month.

Research: Name a specific subject to research.

Instead of a subject to research, you might decide to read a nonfiction book about a topic that interests you or a writing craft book. If you do select a subject to research, consider listing what research you’re planning to do this month, for example, “Read wikipedia entries about the Golden Age of Piracy.”

Release: Name a piece of writing you will release or submit.

Releasing writing into the world doesn’t always need to be to a potential publisher. Many of my release goals will be about submitting works-in-progress to critique partners. You might even decide your release goal is to send a chapter or story to me!

Relax: Name one thing you will do for yourself and your self-care.

It can be easy to forget that a rested mind works more efficiently and creatively. Picking one thing to do each month that is just for you and your mental (or physical) health is about letting yourself rest and recharge so you can later tackle all your other goals.

Download a Writer’s Five Worksheet for yourself. As you set your goals for the next month, consider what you’ve been avoiding, are struggling with, or need some extra motivation to complete. What is the smallest thing you can do to start working on that project? Maybe that’s your first goal.

If you post your goals on Twitter or Instagram, don’t forget to tag @selfwinding so I can cheer you on.

Want a Writer’s Five Worksheet in another color? A whole rainbow is available to patrons pledging $2 or more per month at my Patreon campaign. As a patron you’ll be able to download Bust-Ass Blue, Gangbusters Green, Productive Peach, Vigorous Violet, Can-Do Cranberry, and Successful Steampunk (spoilers: it’s brown), in addition to Tenacious Teal.